These last few weeks, the topics of slut-shaming and sexual extortion have been weighing on my mind. These are huge problems facing girls in schools and I’ve been thinking a lot about how they tie into digital citizenship and the formation of a digital identity. Through watching videos, reading articles, and reflecting, I’ve come up what I think some of my responsibilities are – as a teacher and as a young woman – to support my students in the face of these issues.

Your Body = Your Worth

About two weeks ago, I went to a film screen put on by The UnSlut Project, a project working to undo the dangerous slut shaming and sexual bullying in our schools, communities, media and culture. Here is the trailer for the documentary film:

Emily Lindin started the UnSlut Project in response to hearing stories about suicides of girls like Rehtaeh Parsons, Amanda Todd, and Audrie Pott. She was reminded of how she felt when she was labelled as the school “slut” in her middle school and decided to share her story by posting her diary entries from ages 11-14 online. The Project has become a collaborative space for sharing stories and creating awareness of sexual bullying and slut-shaming.

While watching the film, it stuck out to me that girls are told over and over again that their worth is based on how their bodies look to other people. The media constantly imposes impossible standards of beauty on girls and diet/beauty industries fuel body dissatisfaction to make profit.

It starts scary young. Media Smarts reports that three-year-olds already prefer game pieces that depict thin people over those representing heavier ones, while by age seven girls are able to identify something they would like to change about their appearance.

“The barrage of messages about thinness, dieting and beauty tells “ordinary” girls that they are always in need of adjustment—and that the female body is an object to be perfected”

Media Smarts

And not only are girls told that their bodies are objects to be perfected – they are also told that until they can perfect their bodies and become thin, beautiful, and sexy, their worth is compromised. If they want to be worth something, they need to eat less, workout more, show more skin… The list goes on.

Sexy = Valuable But Sex = Shameful

So this idea that girls must have a perfect body and be sexually attractive in order to be worth something sounds awful when you say it outright; however, these are the messages that the media is sending to young girls, who often receive and internalize them.

And perhaps the most sickening part is that when girls learn the rules of our culture – that their sexual desirability is what makes them valuable – and try to portray themselves as sexy, they are labeled, shamed, and bullied for it. It’s a vicious, grueling cycle and one that many girls, including Amanda Todd, have fallen victim to.

This paradox doesn’t disappear as girls grow up, either. It manifests in double standards that put women down for doing the same things as men (ie. she’s a slut, he’s a stud). Jarune Uwujaren from Everyday Feminism puts it this way: “Ironically, our society simultaneously values women for their sexual desirability and shames them for having sexual desires.”

What’s the point? There should not be worth tied to a woman’s or a girl’s sexiness or how much sex they choose to have. Slut-shaming is extremely harmful to a person’s self-concept and internalizing those negative messages results in tragic outcomes for girls and women.

Constant Pressure, Little Control

Girls are constantly pressured into portraying their bodies in ways that will please others, whether it’s posting pictures to social media, sexting, or revealing themselves to a camera online. But once they share, they have little control over how the images will be perceived or what the viewer might do with the image. The pictures are easily circulated and become part of a digital footprint that remains with them forever.

The Sextortion of Amanda Todd, a documentary by the Fifth Estate, shows the extensive blackmail that the seventh grade girl received after flashing the camera in an online chat with a man she had been messaging with. He was a ‘capper’ – a cyber-predator who stalks websites looking to flatter girls into performing sexual acts and then capture and distribute their images. When Amanda was put under pressure, she made one mistake and the damage was done.

Although the RCMP was notified about blackmail attempts on at least five occasions in the two years leading up to Amanda’s death, they simply told the family: “If Amanda does not stay off the internet and/or take steps to protect herself online … there is only so much we as the police can do.”

This (lack of) response horrifies me. It’s victim blaming and it places all the responsibility for Amanda’s protection on her and her parents’ shoulders. I think it would have been pretty obvious that it was the RCMP’s job to protect Amanda had her harasser been physically stalking and harassing her. Why should it be any less their business when it’s online?

Digital Dualism

I don’t think it’s realistic for us to tell young people to just stay offline when their lives are so intertwined with online spaces. They have grown up in a world of digital dualism, where they interact in two different worlds that are fully, inextricably weaved together. We can no longer separate our digital lives from our offline lives, nor can we expect young people to do this. And avoiding the problem wouldn’t have solved anything, anyway. She couldn’t have stayed offline forever.

Amanda needed someone to teach her how to protect herself and be safe online. She needed someone to show her that she could start to build a trail of positive artefacts (which I think she was trying to do in the famous video where she shares her story) that would someday outweigh the picture that destroyed her reputation. She needed support in rebuilding her self-concept and strategies to deal with her online and offline bullies.

As educators, what are our responsibilities? What can we do about all of this?

1. Speak out about slut shaming and sexual bullying.

We must start with a ground up approach by speaking out within our personal spheres. One strategy suggested by the Unslut Project is to ask the person to define “slut” or to explain what they mean by their problematic comment. The conversation might go something like this: “What do you mean by ‘slut’? “Well.. a promiscuous woman.” “What’s promiscuous?” “Well.. she has too many sex partners.” “So how many is too many? Who gets to decide?” It quickly becomes apparent that no one has any business judging anyone else based on their sex life.

It’s also important to note that women can simultaneously be victims and perpetrators of slut-shaming. This means we need to be critical of our own thoughts and careless comments and catch ourselves when we slut-shame. Through speaking out and listening to one another’s stories, we can humanize each other and begin to work together against this shaming.

2. Help students deconstruct media messages and develop critical thinking skills.

I tried to do this in my internship through a health unit on body image. I had my students examine a variety of advertisements and critique them in groups using a questionnaire. We discussed influences on body image, such as the media, family, friends, culture, place through videos like this and talked extensively about stereotypes related to body image. In fact, this unit turned my students into the Stereotype Police. They became really passionate about reporting stereotypes they heard at home, around the school, and from one another. We also examined photoshop mistakes and saw how photoshop is used to create a problematic “ideal” body type. These are just a few ways we can get students thinking critically about the messages the media sends.

3. Educate students about their worth.

It’s our job to make our students feel loved, respected, valued, and affirmed for who they are and what they do. When we constantly remind students how irrationally crazy about them we are, we help them understand and believe that they are worth so much more than what their bodies look like.

“And when you start to drown in these petty expectations you better re-examine the miracle of your existence because you’re worth so much more than your waistline.”

Savannah Brown

“…Standards don’t define you. You don’t live to meet the credentials established by a madman. You’re a goddamn treasure whether you wanna believe it or not.”

Savannah Brown

I also recently came across this beautiful poem by Rupi Kaur and I think it would be great to share with students:

i want to apologize to all the women i have called beautiful

before i’ve called them intelligent or brave

i am sorry i made it sound as though

something as simple as what you’re born with

is all you have to be proud of

when you have broken mountains with your wit

from now on i will say things like

you are resilient, or you are extraordinary

not because i don’t think you’re beautiful

but because i need you to know

you are more than that”

― Rupi Kaur

These are the kinds of traits we need to recognize in our students and help them recognize in each other. We can model these types of compliments: You are resilient. You are passionate. You are extraordinary. You have such great vision. You are working so hard. I love how you support your group members. Through our words and through the resources we bring in, we can show our students how deeply valuable they are and remind them of their endless potential.

(My focus in this post is on girls, but I recognize that boys also need to be educated about their worth, as they are also affected by the problematic way that masculinity is defined and portrayed by the media. I also recognize that transgender students, probably the most of anyone, need to see positive representations of their identity in the classroom. So although I’m focusing on girls in this post, I truly believe in instilling a positive self-concept in ALL students.

4. Educate students about digital identity and digital citizenship.

Teaching students the how and why behind constructing a positive digital identity is an extremely important responsibility, as professional digital profiles have huge effects on future employability and might even start to replace resumes. The digital footprint students leave will impact them short-term and long-term.

This tweet, from Katia Hildebrandt, is a response to this article, which makes it clear that as a society, we are willing to consider the context and timing of mistakes like DUIs, but unwilling to consider the context and timing of mistakes in the form of hateful social media comments.

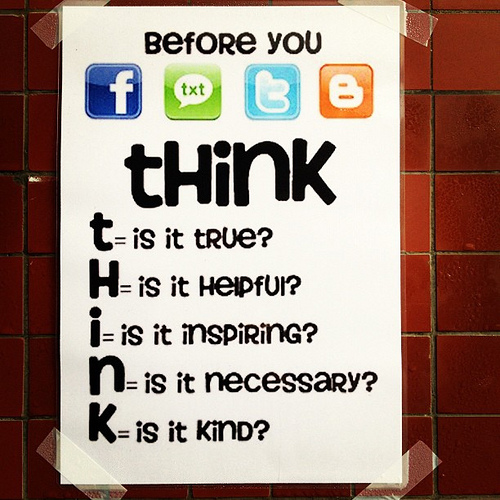

Because their digital actions will continue to affect them throughout their lives and because of the harm we have seen in Amanda’s story, it is imperative that we teach our students to ask themselves questions before they put anything on the Internet. When posting about themselves, we might teach them to ask: Would I want my grandma or future employer to read this? Does this represent me in a positive way? And when posting about others, we might teach them to ask: How would I feel if this was shared about me? Do I have this person’s permission to share about them?

We can also teach them about online predators and the risks of exposing themselves online. We can show them examples of how our digital footprints can easily slip out of our control. Rather than asking students to simply avoid the internet or installing ineffective filters, we need to give them the tools to make responsible decisions for themselves.

5. Educate parents about digital footprints and their child’s digital identity.

Along with educating students about digital identity, we need to educate their parents. Research from the University of Washington finds that while children ages 10 to 17 “were really concerned” about the ways parents shared their children’s lives online, their parents were far less worried. Another study finds that ‘sharenting’ – parents who share details of their family life online – can be detrimental in cases where parents put their online popularity ahead of spending time with their child. We need to model the process of asking students for permission before sharing about them online. We can offer support in helping parents find a middle ground, where they can share about their children online in a way that doesn’t compromise the child’s privacy or dignity.

Throughout the documentary, Amanda’s parents went from supporting her use of YouTube as a tool to share her singing talents to being highly concerned about her online behaviour when her photo went viral and she began to receive blackmail from the capper. Although they documented everything and continually informed the RCMP about the blackmail, they seemed ill-prepared to give Amanda any advice on how to defend herself online or how to start to repair her digital identity.

6. Educate ourselves about the online tools, apps, and websites students are using.

We need to keep up with the online tools are students are using and bring those into our classrooms and schools. For example, young people love Snapchat and there are many ways we can use Snapchat in our schools and classrooms for teaching, communicating, and sharing. We also need to educate ourselves on specific issues related to the tools, apps, or websites being used. For example, I recently became aware of the huge issue of cyber self-harm, a phenomenon in which young people create fake online identities to attack themselves and invite others to do the same. They might do this to pre-empt criticism from others, to bring their pain out into the open, or to get compliments from peers. We need to make ourselves aware of these issues so we can better understand what our students are going through and can support them in the best ways possible.

7. Educate everyone about moving toward a more forgiving digital world.

Finally, because we are living in a world that no longer forgets, we need to work towards greater empathy and forgiveness towards others when they make mistakes online. We need to learn to make informed judgments rather than snap decisions and teach our students to do the same.

This means a few things, which Alec Couros and Katia Hildebrandt outline in their joint blog post. It means thinking about the context, timing, and intent of digital artefacts when we evaluate them. It means considering whether the artefact is a one-time thing or a pattern of behaviour. And it means holding ourselves accountable to the hypocrite test – asking ourselves whether we have ever said or posted something similar and thinking about whether we would want that held against us.

Burden or Opportunity?

My heart breaks for Amanda Todd, Retaeh Parsons, and so many other girls who have taken their lives due to experiences like this. As educators, we have a ton of responsibilities for educating ourselves, our students, and others on these issues. These responsibilities may seem burdensome, but they also place us in a unique and critical position to support students and families as we all learn about digital identity formation and online safety together.

So what do you think? What other responsibilities would you add to this list? What steps can we take to prevent tragedies related to slut-shaming, cyber-bullying, sexual extortion? I’d love to hear your thoughts.