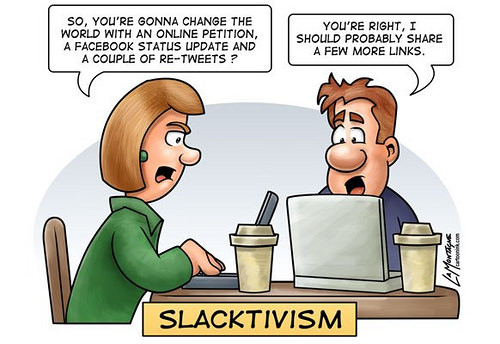

Activism vs. Slacktivism

Social media campaigns have been widely critiqued for reducing activism to hitting the retweet button or sharing a Facebook post. This article suggests that slacktivism can be counter-productive, as sharing on social media might lead you to feel like you’ve done your part and absolve you of the responsibility to do any more. Similarly, Sarah Ross challenges her readers to be critical when they see online activism and asks, “are you willing to go further than the click of your mouse?” Zachary Sellers is also a critic of social media campaigns, claiming that they are ineffective, that they spin messages to their advantage, and that they are more about advertising than action.

I think these critiques are valid and often true, which makes me critical of my own participation in social media campaigns. Is my retweeting and online support always backed up by concrete action? And does it always need to be? Isn’t is also important to speak out about issues to show that they are important and need to be addressed? I know that what I choose to say (and not say) sends a message, so I wonder about the implications of refusing to participate in social media campaigns. Does that silence send the message that those causes are not important? These are questions I’m still wrestling with, and I welcome feedback in the comments section below.

Despite criticisms, it is obvious that some social media campaigns have been critical in raising awareness of issues, creating discussion, generating political will, and bringing about action. 40 million tweets from #BlackLivesMatter were analyzed and found to have been essential in driving conversation about race, criminal justice, and police brutality. The #BlackGirlMagic movement has led to debate, discussion, and supportive communities, which has furthered the topic of representation of Black girls. #MMIW has been used to share stories and to put pressure on the government to launch a national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

So, the main distinction between powerful social media activism and ‘slacktivism’ that I’ve seen emphasized is that online activism is powerful only when coupled with real world activism. I wonder about this. Is it like a formula?

social media campaigns + real world action = meaningful activism?

I’m not so sure.

Problematic Real World Action

Although I understand the importance of retweets being backed by real action, I think it’s also important to point out that “real world action” can also be problematic. Volunteering and charity work can sometimes perpetrate racist, sexist, classist, ableist attitudes and reproduce stereotypes about the very people the work is supposed to be helping.

Examples of this:

- Benevolent voluntourism that perpetuates the white saviour complex

- Disability simulations that equate empathy with acceptance and obscure environmental, social, and attitudinal barriers

Recently, 5 Days for the Homeless took place at the University of Regina. For this campaign, five students slept outside for five nights to raise awareness about homelessness and to collect donations for Carmichael Outreach. It faced a great deal of criticism for sensationalizing homelessness and reproducing stereotypes about homeless people. You can read Carmichael’s response to these critiques here.

My point here is that the activism vs. slacktivism debate is basically irrelevant, as both online and offline activism can be equally problematic and oppressive. Instead of choosing sides, we should be critical of all types of activism campaigns so that we can work to break down oppression and avoid contributing to it. I will be the first to acknowledge that we will often fall short, make mistakes, and contribute to oppression without meaning to. The important thing is acknowledging this when it happens and not say things like: “But I didn’t mean to reproduce stereotypes about homeless people…” or “But I was only trying to help those poor children in Africa!”

Good intentions don’t matter when they are coupled with oppressive actions. In order to do anti-oppressive work, we have to acknowledge our implicitness in oppression and work against it at every turn. This means being critical of ourselves and the way we structure or take part in activism campaigns, in both online and offline spaces.

So how do we move to meaningful activism (online or offline)?

I’m not pretending that I know exactly how we do this or that there are clear steps to “doing activism right.” But I think the most important thing here is that we must operate in solidarity with the people we are advocating for.

Whether it’s through participating in social media campaigns online or taking action in face-to-face spaces, we need to focus on the experiences of those who are marginalized. Instead of focusing on ourselves – our feelings, our good intentions, the cookies we receive – we need to make marginalized voices and stories the driving force behind the work we do. If we don’t listen to these voices and stories, how can we understand the issue or know what work needs to be done?

We need to continuously educate ourselves on the issue we are working against but not expect those who are marginalized to do the educating. They already have enough burdens without us making it their responsibility to teach us about the oppression they face. We also need to continuously educate those who share our identity. For me, that might mean engaging White people in conversations about race or engaging able-bodied people in conversations about how disability simulations can reproduce stereotypes.

Many of these ideas about how to move to meaningful activism came from these great articles:

So You Call Yourself an Ally: 10 Things All ‘Allies’ Need to Know by Jamie Utt

How to Tell the Difference Between Real Solidarity and ‘Ally Theater’ by Mia McKenzie

The Case Against ‘Allies” by Mychal Smith

I’ll end with this quote, from Jamie Utt’s professor:

“If you choose to do social justice work, you are going to screw up – a lot. Be prepared for that. And when you screw up, be prepared to listen to those who you hurt, apologize with honesty and integrity, work hard to be accountable to them, and make sure you act differently going forward.”

These are our responsibilities – to be critical of all the social justice work we do (both online and offline), to focus on and work in solidarity with those we are advocating for, and to learn from our mistakes and do better going forward.